MolScript: A story of success and failure

2014-11-03

A scientific paper I published in 1991 is on the list of "The 100 most highly cited papers of all time". The paper in question is

Per J. Kraulis

MOLSCRIPT: a program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures.

J. Appl. Cryst. (1991) 24, 946-950

The Top 100 list is published in the 30 Oct 2014 issue of Nature magazine. The list contains the 100 most-cited papers in the entire scientific literature since 1900. The MolScript paper is number 82 on the list, with 13,496 citations.

Update! (26 Nov 2014): The MolScript paper is now Open Access! See the J. Appl. Cryst. web site or DOI:10.1107/S0021889891004399.

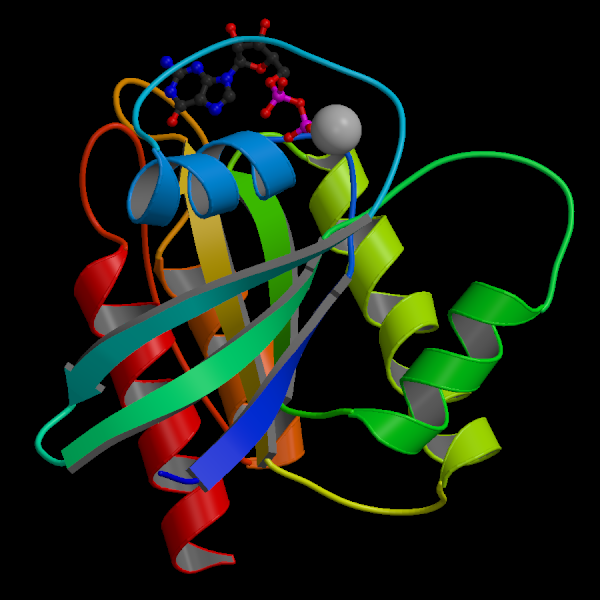

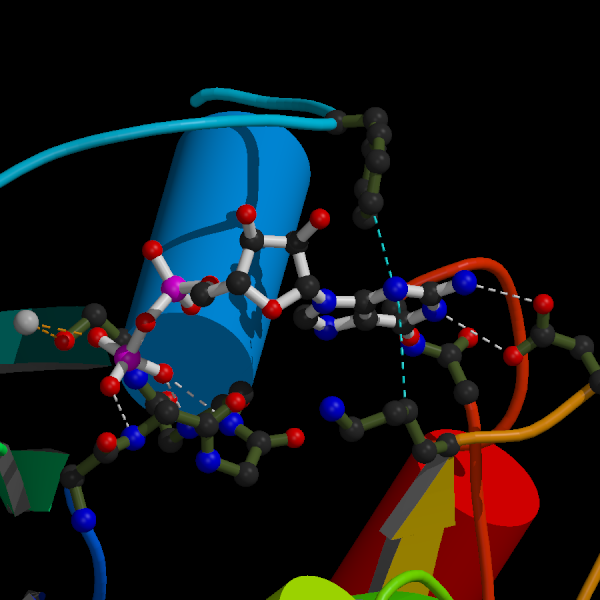

Here are a couple of images prepared using the MolScript program:

This image shows a schematic overview of the ras p21 protein, based on a 3D structure determined by Ernest Laue's group, which I was a member of (Kraulis, PJ, et al, Biochemistry (1994) 12, 3515-3531). The ras p21 protein is a key component of growth signaling in the cell. In a large fraction of cancer cases, this molecule has been mutated, so that its normal regulatory function has broken down.

This image is a close-up of the binding site for the GDP molecule in the ras p21 protein. The dashed lines show some of the important interactions. Both images were ray-traced using Raster3D written by David Bacon, Ethan Merritt, Michael Murphy and Wayne Anderson.

There is an Offical MolScript website, and the code can be downloaded from the new GitHub repository.

I thought it might be of interest to give the background story of the success of MolScript, and also how it has since failed.

Why did I write MolScript?

Science always starts with a problem. In this case, I was preparing my Ph.D. thesis in the fall of 1989 while listening to the radio reports of the crumbling Berlin wall. I needed an image of a protein three-dimensional structure to illustrate a point in my thesis, and I wanted a schematic drawing of the kind pioneered by Bo Furugren and perfected by Jane Richardson (all references are found in the 1991 paper). They drew the images by hand based on the scientific data.

Of course, I needed a computer program; drawing by hand was not an option. The only choice at the time was Ribbon, a program written by John Priestle. Fair enough, but it printed images using an ordinary pen plotter, and the image quality was poor. And worse: It turned out to be impossible to produce an image that included both the schematic view of the protein and the details of a bound small molecule, a.k.a. a ligand.

This was extremely frustrating. The science of macromolecular structures was progressing at a tremendous rate at this time. The lack of a good tool to show the important aspects of a structure, such as the binding site of a small molecule, was a problem when publishing the results of a study. However, I could see no simple way of improving on the Ribbon software, so I had to let the matter rest.

I obtained my Ph.D. in 1989 at Uppsala University with T. Alwyn Jones as my supervisor (who, by the way, also appears on the Top 100 list!). I worked for another year at the department before going on a post-doc. It was towards the end of 1990 that Alwyn got one of the first PostScript laser printers. This was a really nice toy, and a great improvement on the awful pen plotters. PostScript is a proper programming language designed to describe very precisely what to draw and how.

While learning how to use PostScript, I had a revelation: PostScript provided the solution to a problem in computer graphics called hidden surface removal! It allowed me to use the painter's algorithm. The break-through idea was to first produce the schematic object geometrically from the protein structure, then to split it up in small pieces, and finally to output these pieces to PostScript in the reverse order of distance from the viewer. The PostScript printer would then automatically do the hidden surface removal!

Although this was the crucial idea, a number of other factors allowed me to write the MolScript program:

- Alwyn Jones, my boss, was happy to let me spend time on the project. The bulk of the programming took about one month.

- Several people in the lab, which was a joint department of Uppsala University and the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU), helped me in numerous ways. Among these I would like to mention Carl-Ivar Brändén, Mats Kihlén, Ylva Lindqvist, Hans Eklund and Erling Wikman.

- I discovered the Hermite spline curves in the handbook Fundamentals of Interactive Computer Graphics by Foley and van Dam. This type of spline curve, together with some careful geometric construction based on the known stereochemistry of protein structures, produced an aesthetically pleasing and accurate schematic representation.

- I was good at programming, having created several serious pieces of software as part of my Ph.D. work.

- I had just understood how programming-language compilers worked, and I realized I could apply this when designing the command language for MolScript.

How I wrote it and shared it

I started writing the program over Christmas and New Year 1990-1991. I used Fortran 77, which was the standard language in the field back then. From today's perspective, this seems like a horrifyingly stupid idea. But I did it, and the program worked. Only in 1996 did I rewrite the whole thing in the more appropriate C programming language.

I got the program working sometime in January 1991. I tested the program fairly extensively, wrote the paper and submitted it late February 1991. It was published, I think, in late spring.

Almost immediately, many researchers in the field wanted the software. I told them to send me magnetic tape by mail, since the magnetic tape cartridges were pretty expensive. Remember, the Internet barely existed, and the Web had not yet been heard of outside CERN. I copied the software onto the tape and sent it back. When the Web got going, I set up a web site, I think it must have been in 1995, from where MolScript was distributed.

The second crucial factor in the success of MolScript was this: I decided to use a license scheme where academics would get the software (including source code) without charge, as long as they agreed to cite my 1991 paper whenever they published articles with images produced using MolScript.

The use of MolScript that has made me the most happy, I think, was for the fifth edition of Stryer's Biochemistry (2002), which is a classic handbook used in many academic biochemistry courses the world over. Most of the illustrations in it were made using MolScript.

The third crucial idea I had was to charge companies money for the software. A company got the software with source code and a right to make any number of copies internally for a single, one-time fee. I guaranteed nothing with regards to function. I set up the company Avatar Software AB to handle the selling of MolScript. By the way, this was before the movie Avatar! I had read a little about Hindu mythology, and I got the name Avatar from there. I thought that the idea of a god incarnated in a wordly being was a good fit for my company...

During the late 1990s and beginning of 2000s, almost all large pharmaceutical companies, and a number of biotech companies, including e.g. the Kirin brewery in Japan, purchased the MolScript software. It was interesting to see how international companies behaved, confirming national stereotypes: American companies sometimes requested ridiculous legal paperwork, demanding that I indemnify them from everything and anything (I refused), and then sometimes not paying until after numerous reminders. Japanese companies often payed immediately, well before the due date of the invoice.

The money coming into Avatar Software AB allowed me to buy some pretty expensive computers, such as the SGI O2, an outstanding graphics workstation, for my workplace at home. In addition, the accumulated money allowed to me stay away from the Unemployment Insurance Agency (Arbetslöshetskassan) in the bad years of 2007 and 2008, when I was unemployed.

The failure: giving up on the MolScript program.

In 1998, I changed jobs within Pharmacia from protein NMR spectroscopy to bioinformatics. This meant less work with protein structure, and more with computer software as such. So I had less time, and also less interest, to work with protein structures. I essentially let the MolScript program slide after 1999.

Also, during the early 2000s, a number of competitors made their appearance, such as PyMOL. I was simply not interested enough at this stage to compete. This is basically the reason MolScript is no longer used nearly as much as during its heyday around 2000.

Should I have done things differently? In hindsight, one obvious issue is that I never bothered with setting up a proper community of interested persons to develop MolScript. I got some terrific boost from other people such as Ethan Merritt (Raster3D), Bob Esnouf (a separate much improved version) and others, but I did not nurture this. Alternatively, I could have chosen to develop Avatar Software AB into a broader scientific software company, but I was too comfortable in my position at Pharmacia. Given the cut-backs later at Pharmacia and its successor Biovitrum, that was a false comfort.

I have now, at long last, made MolScript into proper Open Source (the MIT license). It is available at GitHub. One never knows, maybe someone wants to take it further? Please do! I think MolScript can be revived in a web services setting. I certainly think that the geometric construction of the schematic objects in MolScript is noticeably better and more carefully done than what the competitors achieve, even today...

Perspective and conclusions

It is a fairly common attitude to say: But what's so great with MolScript (or any scientific software)? It hasn't changed our scientific view of the universe. It's just a piece of software. Anyone could write it.

To which I say: Oh yeah? So why hasn't "anyone" written it? If it's so easy, why aren't you on the Top 100 list?

But to be more serious: Software, as well as methods in general, is an integral part of science. Break-throughs in understanding the universe cannot be achieved without supporting technologies. There is a problematic tendency in mainly the biomedical sciences to underestimate the importance of good software engineering for success in science. The attitude in e.g. physics and astronomy seems to be somewhat better in this regard.

The reasons for the success of MolScript fall into two categories:

- I had a specific problem and the right knowledge, skills, ideas and drive to find a good solution to it. I also happened to choose a very good licensing scheme.

- I happened to be located in the right place at the right time to actually get the thing done. The environment was supportive, including equipment as well as general attitudes, rules and atmosphere.

And the failure of not maintaining and developing MolScript is, of course, due to my own choices. If I had taken another path, MolScript could potentially have been the basis for an expanding company. We will never know.

Having the MolScript paper as number 82 in the list of the most-cited research papers ever is rather nice, so I do consider the MolScript story as a success, all in all.